The Society of the Cincinnati

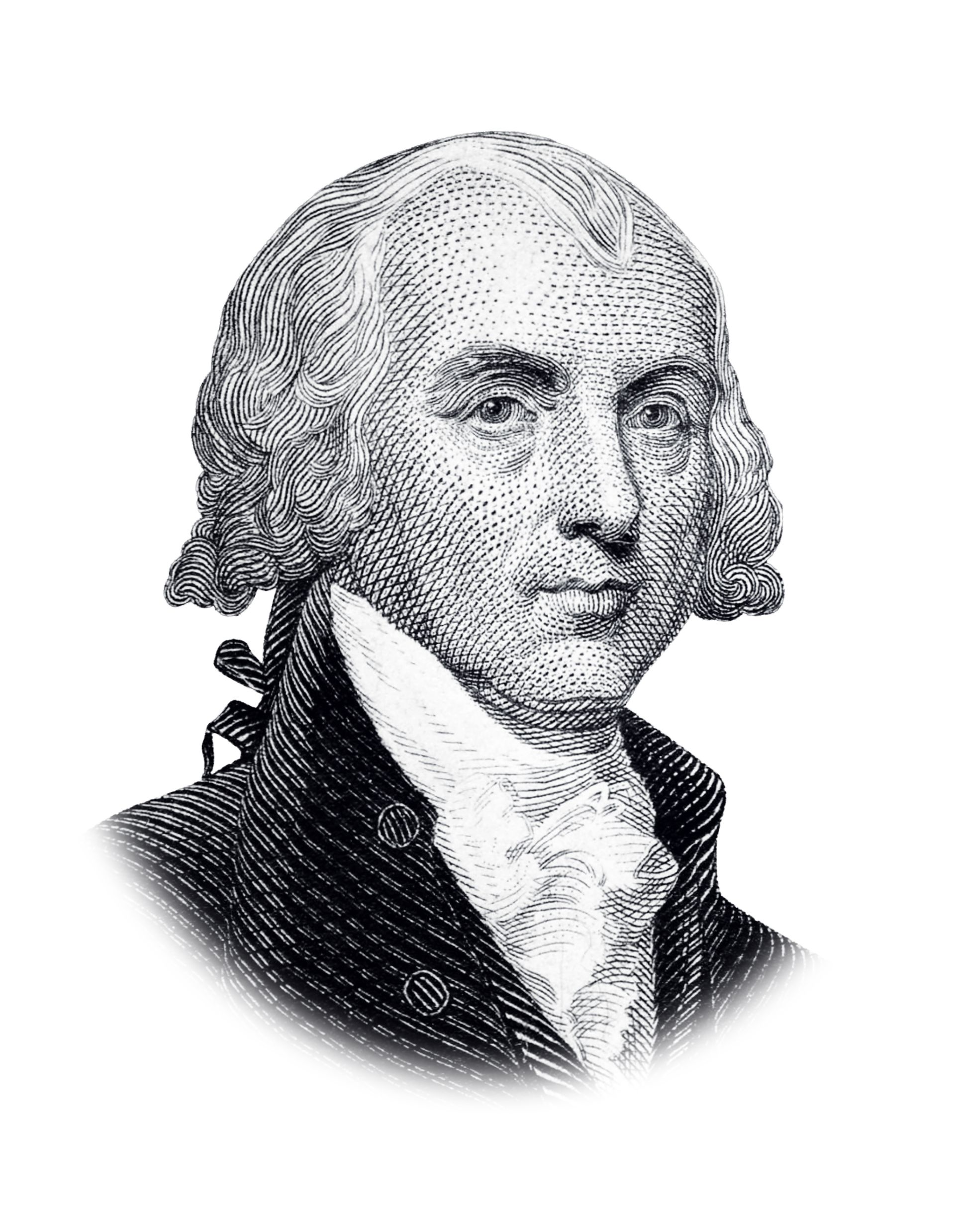

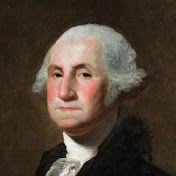

We all know that George Washington was President of the United States for eight years, from 1789 to 1797.

Few remember, however, that he held another presidency twice as long. For the last sixteen years of his life, from 1783 until 1799, he was President of the Society of the Cincinnati.

The Revolutionary War did not end abruptly with the defeat of Cornwallis at the Battle of Yorktown in October, 1781. Matters dragged along in a state of episodic conflict and general uncertainty about the outcome, while England and France quarreled about their remaining positions in North America, and John Jay maneuvered to extract for the thirteen colonies, now to be states, the most favorable possible terms. Washington did not officially declare the war at an end until April, 1783.

It was during this period that events led to the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati. The weak Continental Congress had no taxing power, and was unable to enforce its calls upon the states for funds. As a result the soldiers and particularly the officers had received little or none of their promised pay. Many officers came to feel they could achieve their rights only by force of arms. Their resentment was fanned particularly by General Horatio Cates, who hoped at this late date to displace Washington as Commander in Chief.

At a meeting of officers called by the conspirators at the winter camp at Newburgh, New York, on March 15,1783, Washington famously appeared, and appealed successfully to the patriotism of the officers, effectively quashing with one dramatic address a potential military coup. On April 19, the eighth anniversary of the Battle of Concord, Washington proclaimed the cessation of hostilities, and that same month General Henry Knox was organizing the plan for a Society of the Cincinnati. Cincinnatus was the Roman hero called from his farm to save the republic, who after victory returned to his farm and his plow, disdaining the power he might have seized. The American officers thought of themselves as so many Cincinnati, “beating their swords into plowshares.”

The stated goals of the Society were preservation of the liberties for which the members had fought, charitable help to needy officers or their families, and maintenance of their mutual friendship. A very real, if unstated, goal was to work through political, rather than military means, to secure the promised back pay. For years Knox had thought about such a society, and even its insignia. Now it was Pierre L’Enfant, much later famous as the planner of the city of Washington, who was entrusted with the task of designing the insignia and having the first ones made in Paris.

The goal of caring for widows and orphans of deceased officers and helping those who had been impoverished by the war involved allowing sons of deceased members to become members. This led people like Jefferson, who had never gone to war, to oppose the Society as the beginning of an hereditary nobility. Washington’s overwhelming objective, that the officers proceed by peaceful political means to seek their rights, led him, although very reluctantly, to accept the presidency of the new organization. Once involved, he could never extricate himself. His leadership, however, was probably responsible for the existence and survival of the Society.

As the years passed and Revolutionary officers died one by one, the Society began to fade away. It is a federation of thirteen state societies, one in each of the thirteen original states. In addition a French society is made up of officers of Rochambeau’s army and the French Navy at Yorktown. Early in the nineteenth century many of these fourteen societies faded into more or less complete desuetude, but enough survived that when interest began to return in the mid-century, it was a matter of revival, rather than complete reconstitution of the organization.

Today, the Society, made up of descendants of the Revolutionary officers, is flourishing, with several thousand members and a magnificent mansion in Washington, the legacy of a member, Larz Anderson. He build Anderson House as a home, but with this disposition in mind. The building not only serves as a headquarters and meeting place, but also houses a museum and a magnificent research library concentrating on eighteenth century military history, particularly our Revolution.

The insignia, has a depiction of Cincinnatus with his plow and the motto, “He gave up all to serve the republic.”

John A. Washington

Published in 2006

Washington Words